TL;DR

- We need better metadata management for the container supply chain to better reason about it.

- The OCI specification currently doesn’t have ways to package container image artifacts or a group of container images. But they will get there slowly.

- Meanwhile, we need a package manager for container images.

Some Background

I maintain an Open Source project called Tern which generates a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) for container images. A good number of software components that get installed in a container image are individually downloaded rather than managed via a package manager. This makes it very difficult to figure out the intent of the person or organization that created the container image. It also doesn’t give much information about who contributed to the container image. Most container images are based on previously existing container images, which isn’t that obvious from the client tools or registries. I figured this problem of managing container metadata could be solved if there was a “package manager” for container images. So I brought up the idea of “packaging” back at KubeCon 2018, where I asked whether a container image manifest could hold all this information such that a tool could make inferences about the container supply chain.

It turns out, the community had already been thinking about how to manage things like helm charts, OPA policies, filesystems, and signatures. This is how I had come to be involved in the Open Container Initiative (I still owe @vbatts a solid for introducing me). At the time, it was understood that the container image does not need to be managed beyond identifying it by its digest. No dependency management is required as all the dependencies are bundled into the container image. Updates are dealt with by rebuilding the container again and keeping a rolling tag which downstream consumers can pull from.

However, the container ecosystem doesn’t offer much beyond portability. Managing container metadata along with the container images provides valuable information about the supply chain to consumers and contributors. Two years and several supply chain attacks later, we are still having conversations about how best to do this. Here, I try to boil down some proposed concepts and see how they hold up to our requirements for metadata management.

Back to Basics

There are 3 reasons why one would write a package manager:

- Identification - to give your new bundle of files a name and some other uniquely identifiable traits.

- Context - to understand where your bundle sits in relation to the other bundles everyone else has put out there (i.e. dependency management).

- Freshness - to make sure your bundle gets updated while maintaining its place in the ecosystem.

There is actually a 4th reason - Build Repeatability - which I think falls under “Context”, but it is worth mentioning here because knowing the state of your bundle at a given time is necessary for you to be able to reason about a past “good” state and a present “not-so-good” state, i.e., bisecting a build.

The container image ecosystem has none of these features due to some (well intentioned) assumptions. A container can be “identified” by its digest. You don’t need to manage an ecosystem as the whole ecosystem is already present in one unit. You don’t need to update the container - just build a new one and whatever needs updating will hopefully get updated. This works as long as nothing changes under your application. However, if you plan to maintain your application long term, you must be prepared to deal with stack updates and major releases. We currently do not have a good way of managing stack updates beyond “pulling from latest” (a notable exception is Cloud Native Buildpacks but we will focus on the generic case here). Breaking changes down the stack may block you from re-building the image, forcing you to keep a stale image around, because that image is known to work. As you can imagine, maintaining a fleet of container images becomes more painstaking. It would be really nice if the information required to maintain a fleet of containers and beyond came built-in and available when needed.

Container Registries for Metadata Management

We could build a separate metadata storage solution, but container registries already exist. With some enhancements, they could be used to store supplemental metadata along with the container image. Organizations are already doing this with source images that contain source tarballs, and signature payloads such as what cosign does. The nice thing about using registries is that the metadata can be stored along with the target container image. Proposals to the OCI specifications mostly involve structuring and referencing such data. This is basically package management on the server side. It is difficult to get these proposals merged because the client-server relationship as it currently exists is very tight. Any change to the server impacts the client and any changes to the client’s packaging mechanism affects the server. As a result, the OCI specifications as they stand cannot include enhancements beyond extending the current specification that is in sync with the way Docker clients and Docker registries currently work.

This article is not meant to criticize the state of the ecosystem right now, but rather to lead the conversation to a position where the community can maintain their container images more sustainably. A selfish reason on my part is to also demonstrate the need for package management in the container image space, even if container registries can support linking of related artifacts to container images, and links among container images themselves. Package Management in other ecosystems have a client-server relationship as well, so it’s not new for the architecture to share the burden between client and server. The relationship, in this case, may just be a little different.

Identification

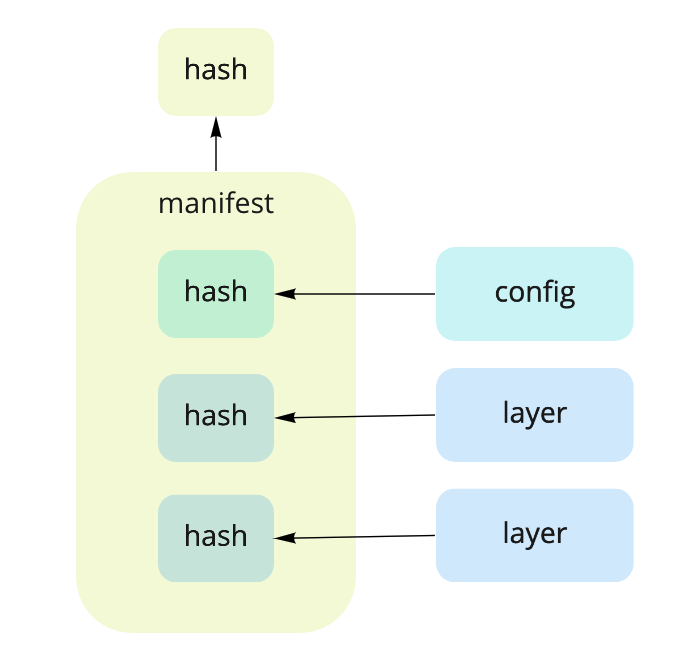

A container image works somewhat like a Merkle Tree with 1 chunk of data, the Image Config, and 1 or more chunks of data representing the container filesystem. Each of the chunks are hashed and placed in an Image Manifest, which is also hashed.

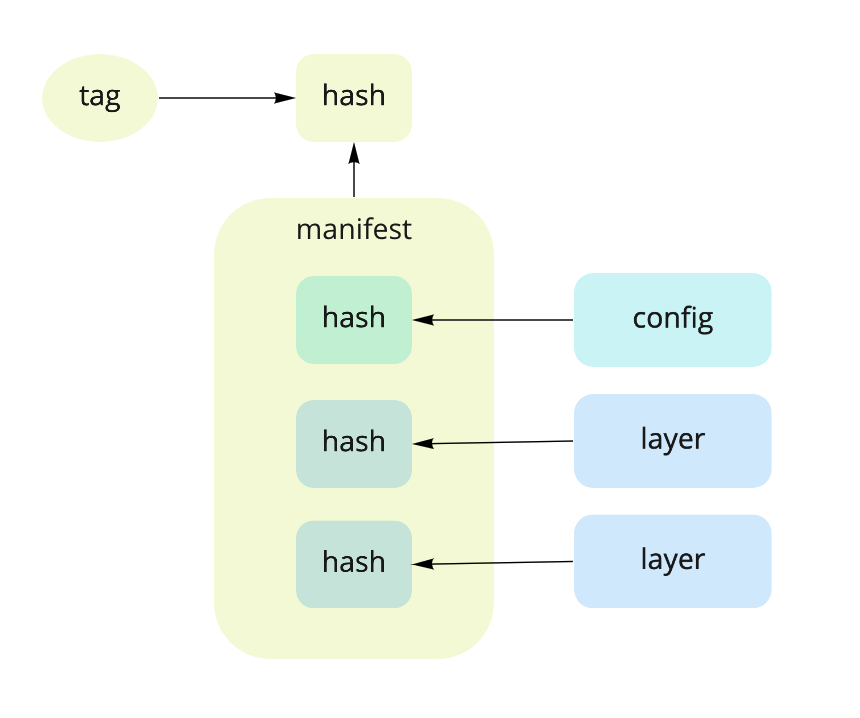

Now, this is all well and good to specifically identify this bundle, but it is missing other identifiable traits, most notably, a name and version. In the container world, the name is the name of the repository and the version could be a tag.

Just like git, all references to file collections are hashes and other references can point to them like HEAD or FETCH_HEAD or a tag. The tag could follow semantic versioning and could be moved to another commit. In the Open Source world, nobody does that because it breaks an inherent contract between the maintainers of the code and the rest of the community. Container image tags do not seem to follow semantic versioning as a rule, but a lot of language package managers rely on it, so there may be some hope in tagging images with semantic versioning tags. Regardless, the hash is a pretty good identifier of the container image.

So what about other identifiable traits? Here are some traits that other package managers use:

- License and Copyright information

- Authors/Suppliers

- Date of release

- Pointers to source code

- List of third party components (starting OS, installed packages)

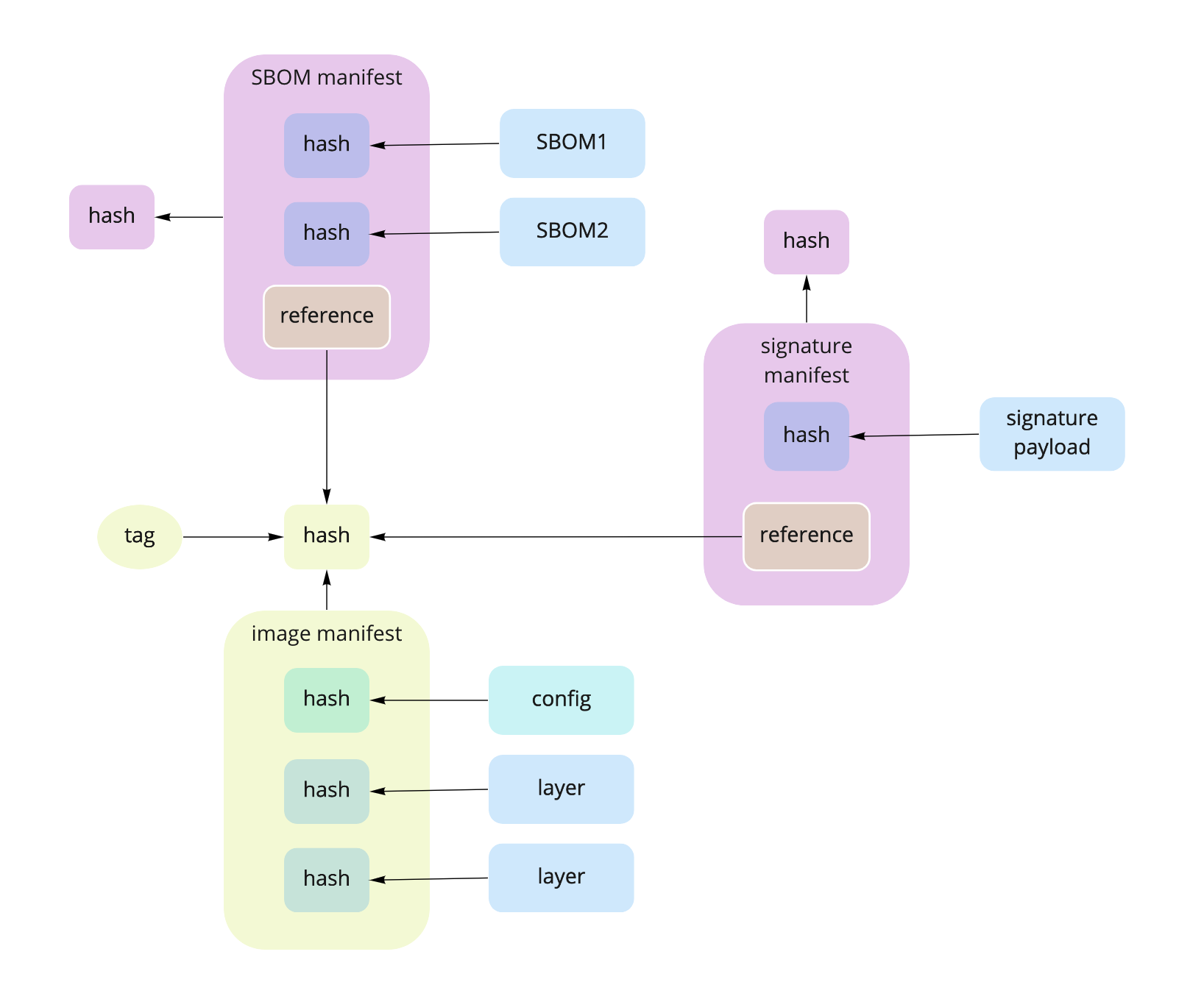

That last one can get pretty long as the number of actual third party components that contribute to creating a container image can run in the hundreds. Lately I have been advocating for putting all this information into an SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) that follows the container image. Container image signatures are another artifact that could travel around with the container image, such as a detached armored signature of the image manifest or a signature payload.

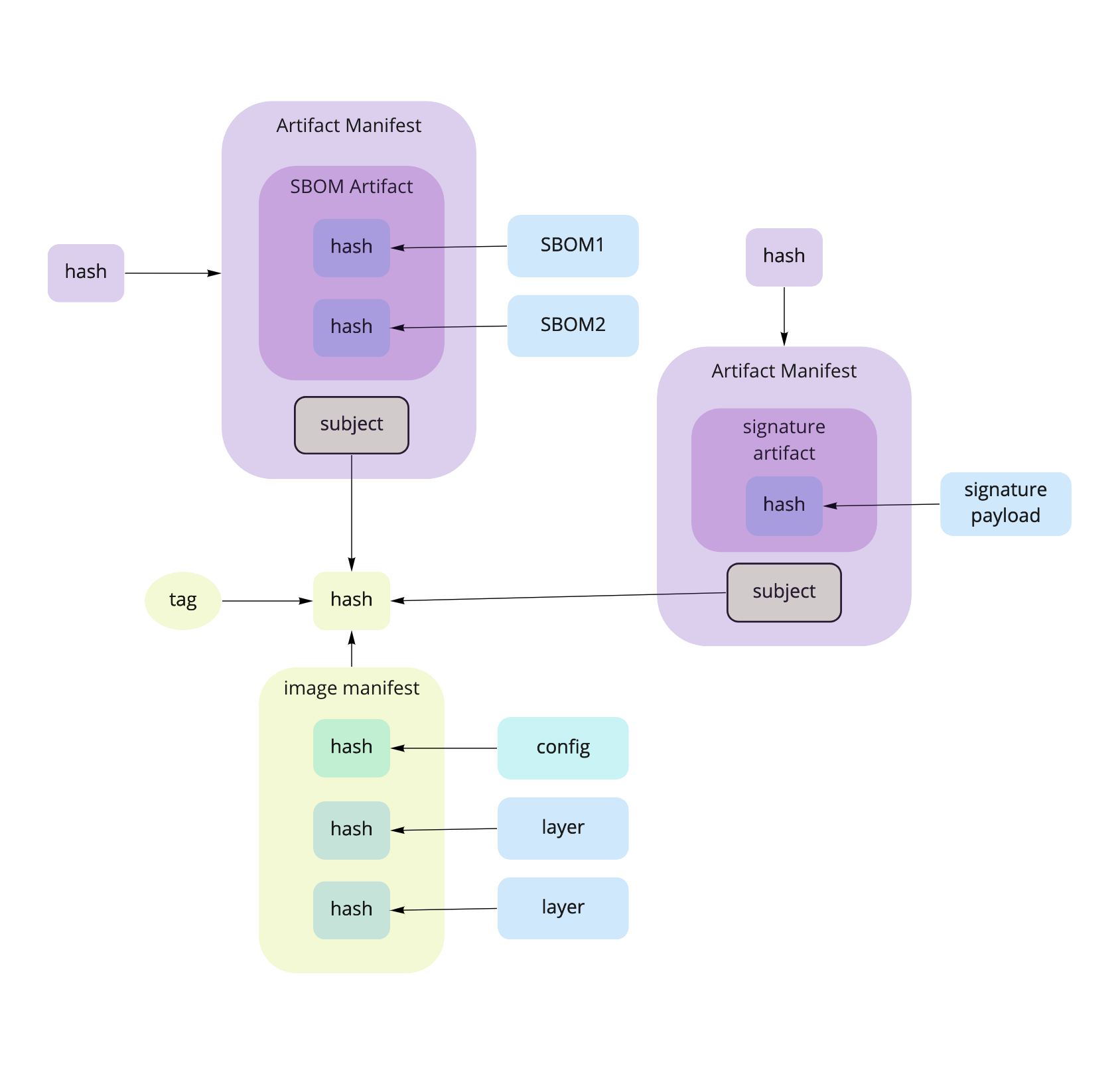

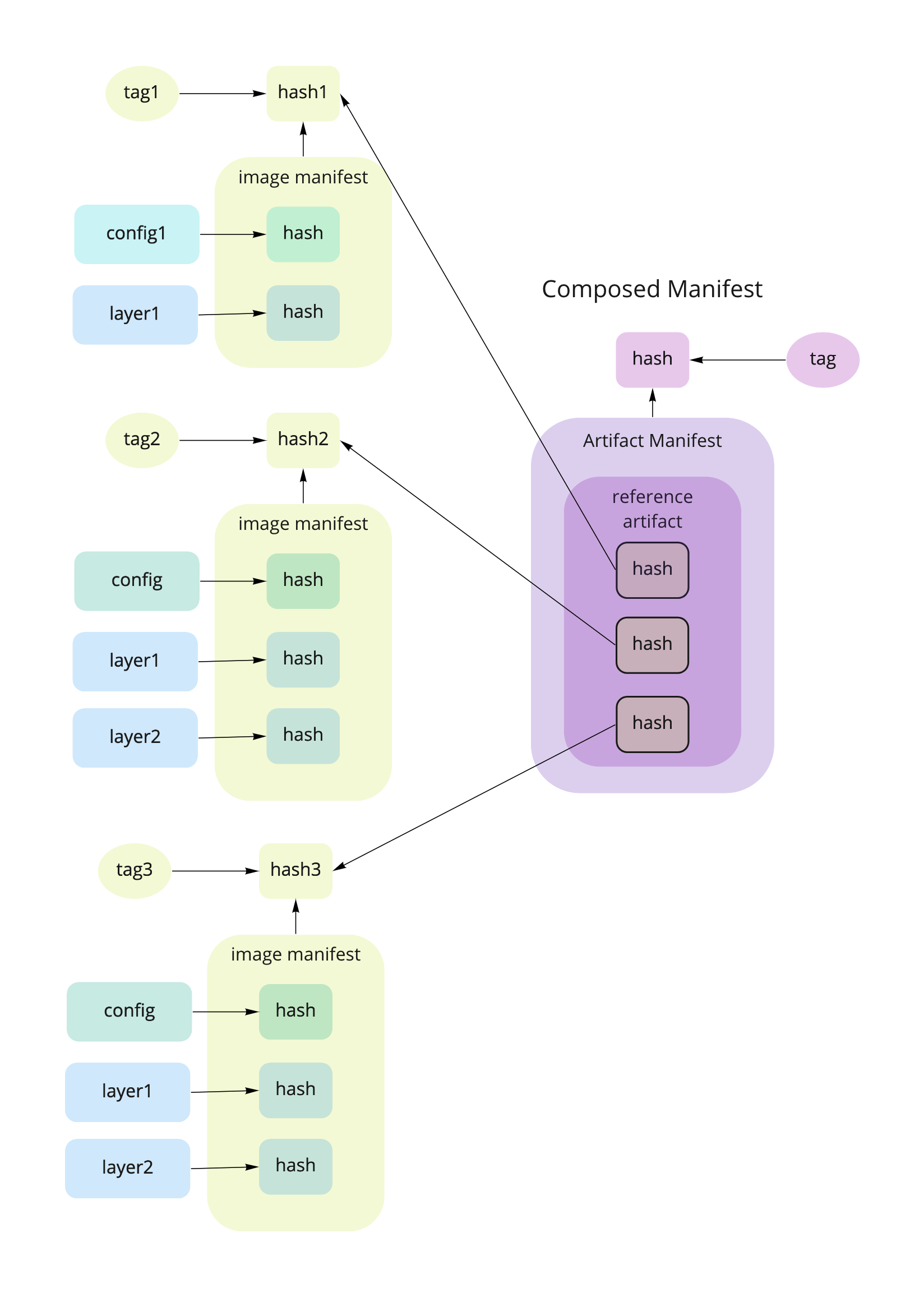

We now have multiple identification artifacts for our container image that we would like to link them to the container image. The current OCI proposals uses “references”. A “reference” is just a manifest containing the hash of the blob and the hash of the manifest it is referring to. In our case here, the reference is to the image manifest hash.

There are still some problems with this layout:

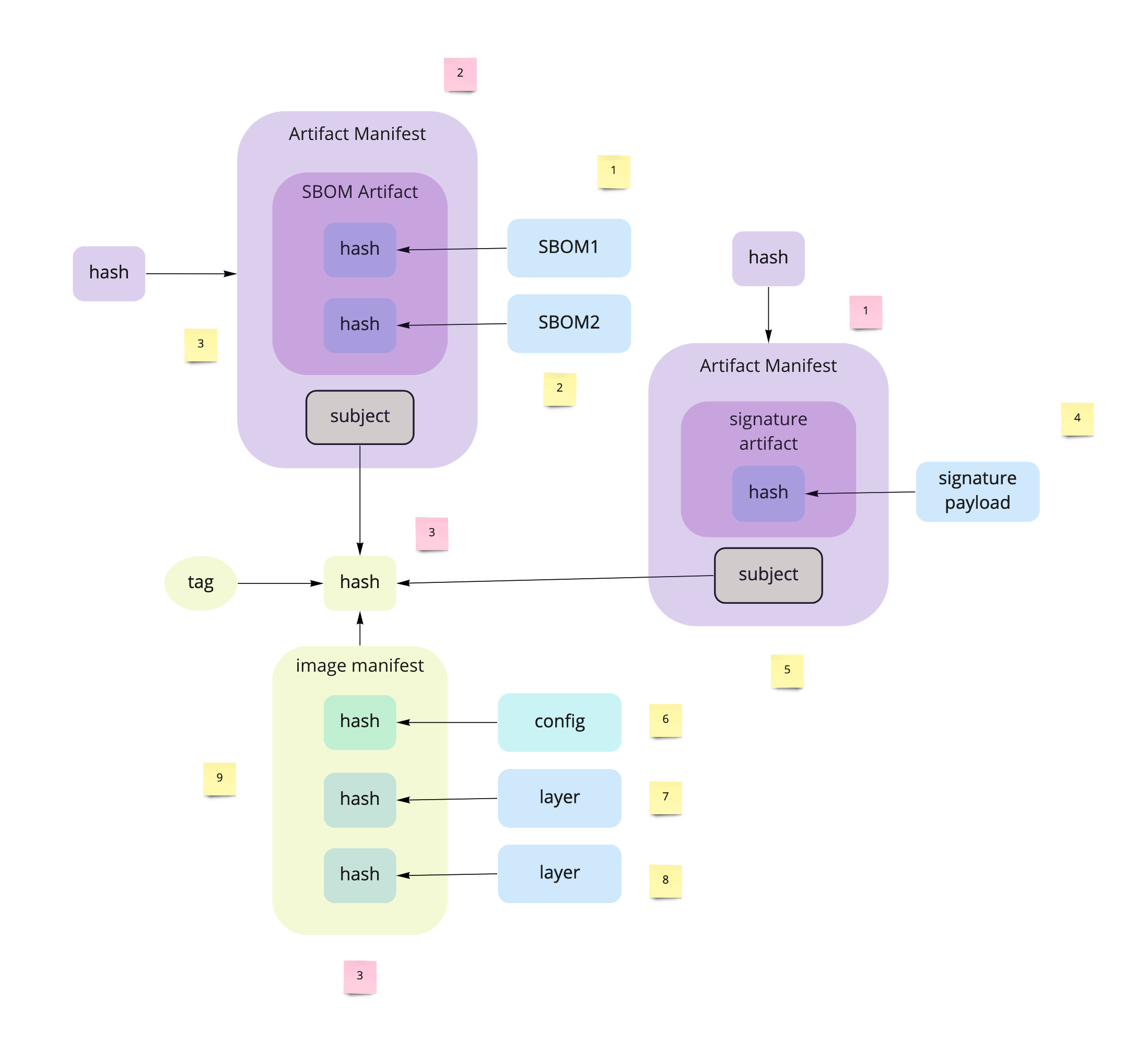

- Registries may only recognize artifacts that are tagged and hence will delete anything that is not tagged.

- Deleting the image results in dangling references.

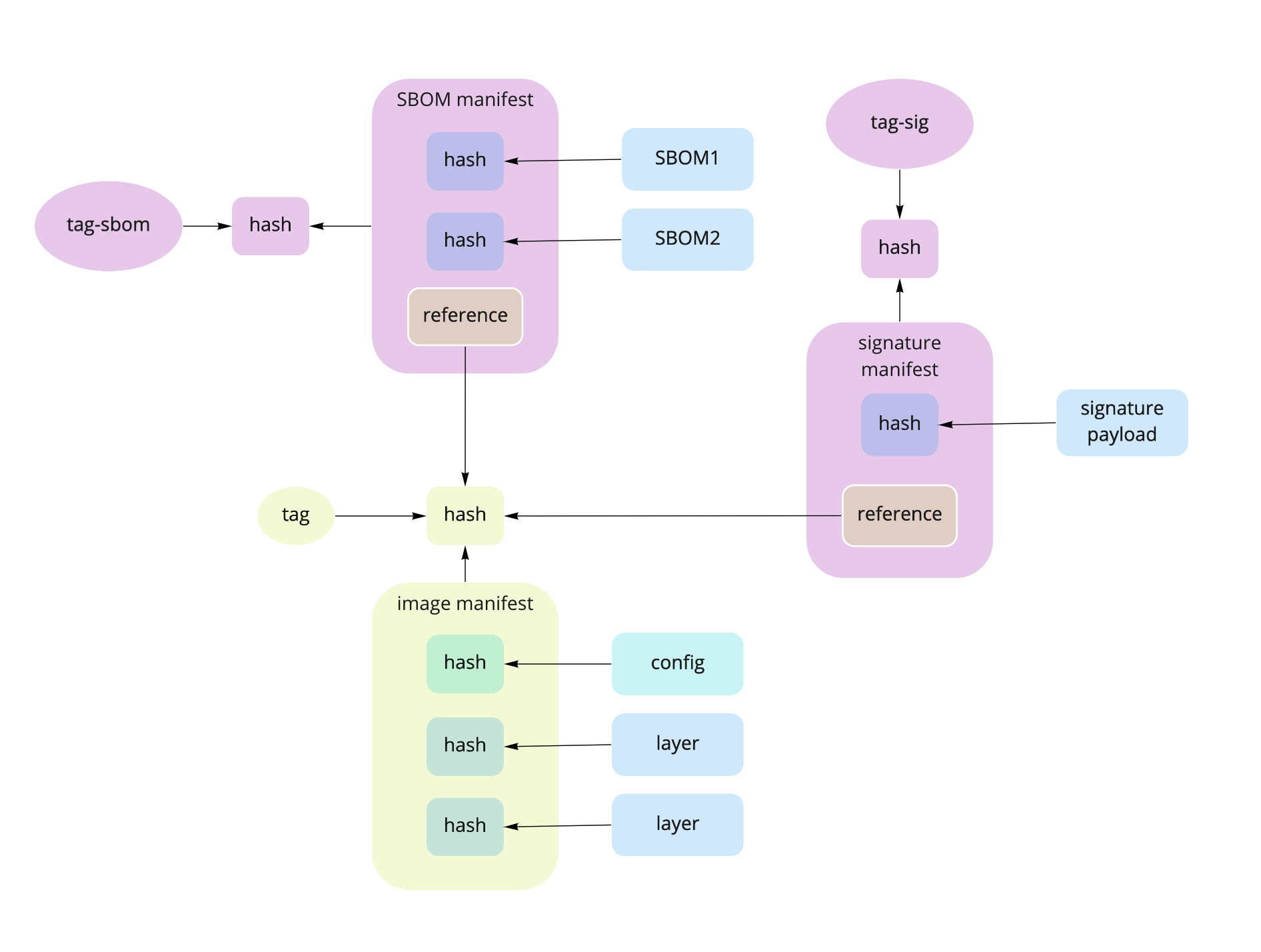

A quick solution may be to tag all the manifests.

This means something needs to be able to keep track of the tags and their relationship to each other, along with keeping track of the versions of all of the artifacts.

A longer term solution may be to define a canonical artifact manifest that the registry will recognize and treat as something special. If that is the case, then something needs to either count or keep track of the number of references associated with each manifest.

Registry implementers can keep track of the links in the diagrams in any way they want. For example, in this diagram, the number of references to each of the manifests are kept track of (minus the hash), and when the image manifest is deleted, the operation walks down the tree to the end of each of the references and deletes them in some order until the number of references is 0.

But here, we are getting into some sophisticated tracking system for all the related objects. This is package management done on the registry side. An argument can be made to maintain a neutral garbage collector that can be used either by the registry or the client, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves. I hope this is enough to indicate that there is a need to keep track of collections of artifacts, either on the client side or the server side, or both.

Context

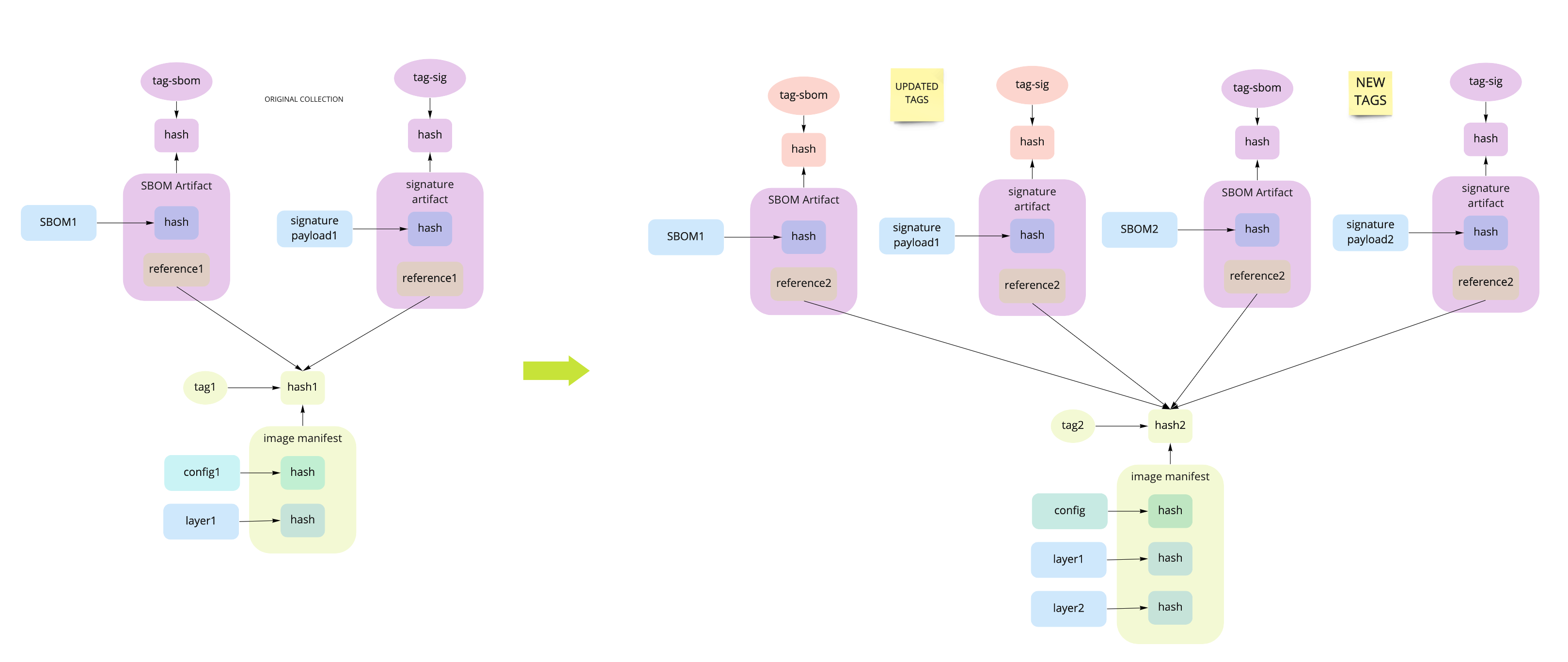

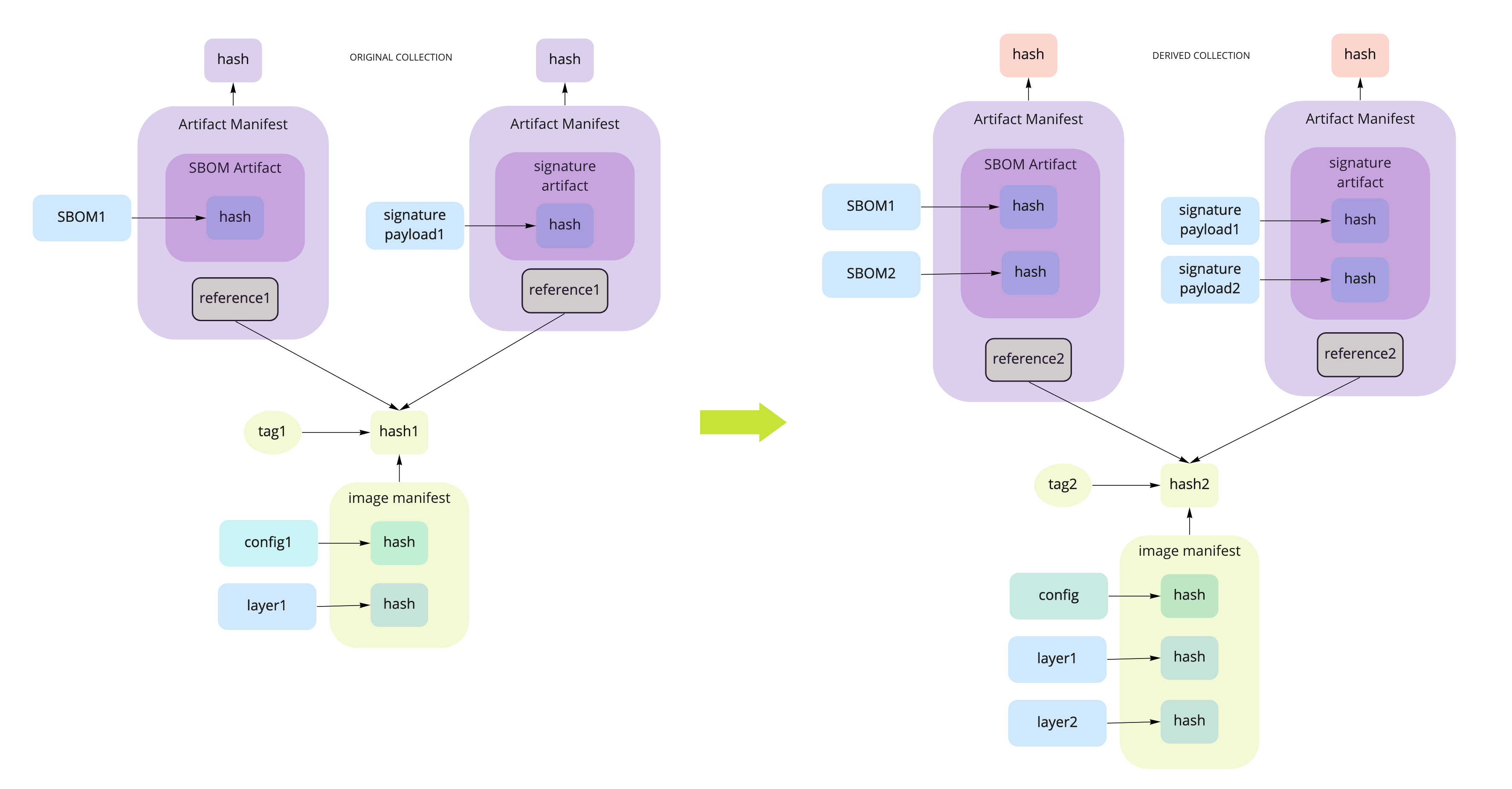

It is understood that a container has no external dependencies at run time. At build time though, the final container image does depend on the state of the starting container image, the FROM line in a Dockerfile if you will. Due to the magic of Merkle Trees, the derived image has no connection to the previous image. As a result, all references to the old image need to be recreated for the new image, as well as adding additional artifacts.

The artifact manifest mechanism may have an advantage over the plain reference mechanism because the number of references are kept at a minimum while the artifact metadata gets updated.

Both mechanisms support requirements such as supply chain security, chain of custody, and pedigree checks. Both mechanisms require reference management. In the former, a client would have to copy over the SBOM and signature manifest of the original image, update its references, and add new manifests. In the latter, a client would have to download the artifact manifests, augment them, and push them along with the new container image. Either way, a client needs to understand some syntax, either with the tag names or artifact construction and artifact types, not to mention some understanding of the ecosystem the artifacts came from (SBOMs and signatures are only two of the commonly used artifact types that could be included).

One use case I had been mulling over is how to link a collection of images together to describe a Cloud Native Application. For example, the Jaegar application is actually a collection of containers that have their own dependency graph. It would be nice describe these connections in a format that can be uploaded to a registry so the whole application can be transfered across registries along with their supplemental artifacts.

Here is where I am at the edge of my imagination (and my diagrams are getting too complex). But I hope these use cases illustrate that if a package manager is not needed now, it will be needed soon in order to manage these high level relationships.

Updates

This is one place where I hope Semantic Versioning would be taken more seriously. Package managers use semantic versioning to allow for a range of versions that are compatible across the stack. This allows downstream consumers to accomodate updates with minimal disruption. As it stands, since container images can only be identified by their digest, the tags are the only way to indicate what version the container is at. This is where package management would be really helpful. Typically, a client queries a server to see if any packages required by an application has a new version. The client then tells the user that an update is available if they want to download it. If the user has a range of versions their application is compatible with, the client just downloads the new version within the range constraints.

The current distribution spec supports listing tags. Beyond that, the registry offers nothing in the way of managing updates, and perhaps, this is all that is needed from the registry side. What that means is that the brunt of the work to check and pull updates falls on the client.

Next Steps

The community is in agreement that these proposals are quite large for the specification to accept at this time. However, there will (hopefully) be a set of public conversations that will try to break down these changes into ingestable bites such that it allows for backwards compatibility with the current state of affairs and moving the specification forward to address all of our concerns. Perhaps in the future, there would be no need for a package manager as the registry and the image or artifact format would take care of providing all of the data required to reason about the supply chain. But that future is far away. In the meantime, we need something that picks up the slack, i.e. a package manager.

Acknowledgements

Many many thanks to @SteveLasker, @jdolitsky, @jonjohnsonjr, @dlorenc, @tianon, and @vbatts for their help in getting me to this level of understanding of the OCI spec over the course of two years.

This platform doesn’t comments enabled, so if you want to follow up on this article, you can reach me on Twitter. Thanks for reading!